Volume 7 Issue 2

The Critical Role of Crisis Resilience in Building and Sustaining Political, Economic and Social Stability

By Benjamin J. Ryan, Deon V. Canyon, James Campbell, Frederick M. Burkle, and Wie-Sen Li

Introduction

The increasing complexity, and multidisciplinary and transboundary nature of modern-day crises require the security sector to work with those in clinical care, public health, diplomacy, law, politics and the social sciences to build and sustain stability across the Indo-Pacific. The 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda, including the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (SFDRR), the Sustainable Development Goals, the Addis Ababa Action Agenda, the Paris Agreement on climate change and the New Urban Agenda provide a platform for the security sector to actively support political, economic and social stability.[1] The 2015 SFDRR for the first time established community “resilience” and well-being as an explicit outcome.[2] The 2005 Hyogo Framework for Action (HFA) signed by 168 nations, also called on “specific actions” focused on “building the resilience of nations and communities through disaster risk reduction, improving risk information and early warning, building a culture of safety and resilience, reducing risks in major sectors and strengthening preparedness for response”.[3] These agreements recognize the important role all sectors and levels of government can play in development, which underpins resilience.[4] Successful implementation depends on a whole-of-society partnership.

For the Indo-Pacific to build and maintain crisis resilience, implementation is required at regional, national, provincial and local levels. However, without a resilient local government and community, national and provincial resilience is not possible. This is because the local community levels are most intensely and immediately impacted by a crisis. The first responders work and live in communities affected and are best placed to understand the context that shapes their priorities and needs. All communities are different, with varied geography, critical infrastructure and population risks and vulnerabilities. Enhancing community resilience and taking responsibility for that resilience extends to the “anticipation and assessment of threats”.[5] Ultimately, resilience depends on the capacity, competence and willingness of local governments and their communities to sustain and advance strategies that integrate crisis mitigation and adaptation.[6]

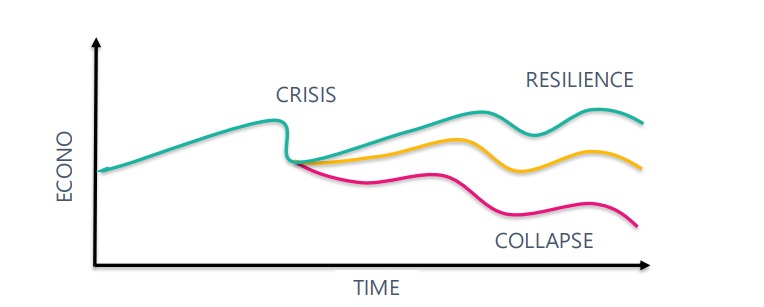

Figure 1 - Crisis resilience model

Source: Ryan & Campbell, Comprehensive Crisis Management for Security Practitioners: Structures, Systems and Policies (Honolulu, HI: Daniel K. Inouye Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies, 2018).

Key characteristics of a resilient local government include the ability to resist, absorb, accommodate, adapt to, transform and recover from the shocks of a hazard in a timely and efficient manner (Figure 1).[7] In this context, a hazard is a process or phenomenon (for example, cyclone, earthquake or ecosystem decline) that may cause loss of life, injury or other health impacts, property damage, social and economic disruption or environmental degradation.[8] Increasingly in the context of cities, resilience is framed around the ability to withstand and bounce back from chemical spills, power outages, as well as chronic stresses occurring over longer time scales, such as land salination, groundwater depletion, deforestation, or socio-economic issues such as homelessness and unemployment.[9]

Urbanization and the complex characteristics of local governments can present opportunities for crisis resilience, while at the same time they have the potential to increase vulnerabilities and risk.[10] For example, 80% of the world’s largest cities are vulnerable to severe impacts from earthquakes, 60% are at risk from storm surges and tsunamis, and over 50% of the world’s population now reside in cities, with this expected to increase to 66% by 2050.[11] Rapid urbanization, common to the Indo-Pacific puts pressure on land and services if not accompanied by sustainable planning and appropriate land-use decisions. Rapid unsustainable urbanization occurs where incoming populations settle in hazard-prone areas such as coastal lowlands, floodplains or unstable and steep slopes.[12] The individuals and households in these populations experience reduced resilience compounded by compromised local infrastructure, which increases the risk of a destabilization and even societal collapse.

Large urban areas also represent complex systems of systems, dependent on robust, uninterrupted, external connectivity for transportation, commerce, energy, communications, food, water and other resources. This interdependency creates unique public health vulnerabilities, such that a shock that is large enough and central enough to the national government and key societal institutions can spread like contagion through interconnected systems, potentially even leading to catastrophic failure of fragile states.

To provide a basis on which to build and sustain political, economic and social stability across the Indo-Pacific through resilience, this paper describes: crisis resilience; the importance of engaging local governments; benefits for the security sector; strategies to build and sustain resilience; and recommendations to enhance political, economic and social stability.

What is Crisis Resilience?

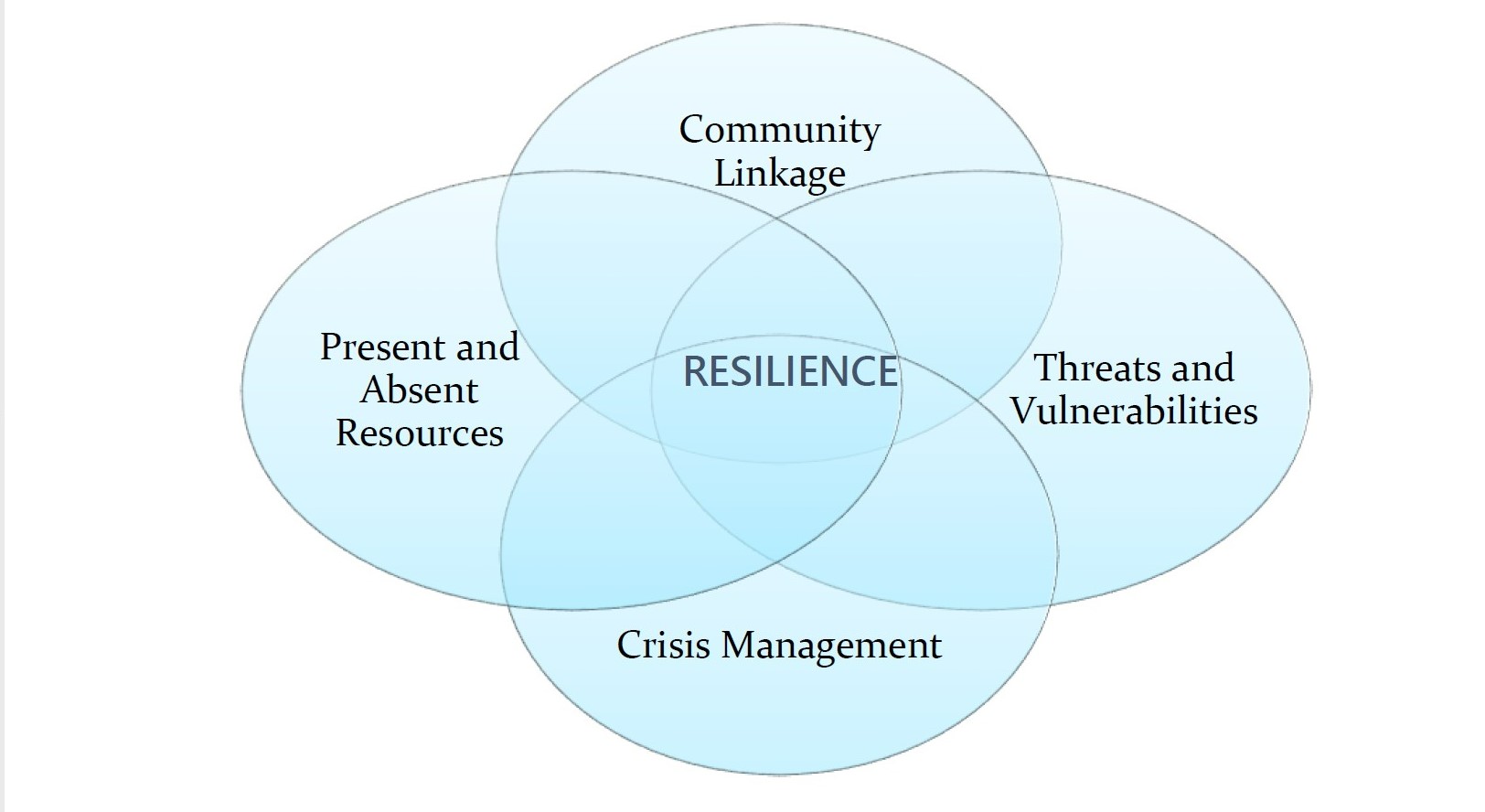

There are four interacting theoretical dimensions, which make relatively equal contributions to achieve the concept of crisis resilience (figure 2). These include the level of: community linkage (e.g. social connectedness and cohesion); threats and vulnerabilities (e.g. risk of exposure to disaster, drought, famine, health status and unemployment); crises management (e.g. command, control and coordination structures); and present and absent resources (e.g. forests, food supply, education, employment and water). All local governments possess these dimensions to varying degrees and are used to respond to one or more disruptive events. However, if weakened to the point of failure, crisis resilience deteriorates as indicated in Figure 2, increasing the risk of destabilization and societal collapse. Weakening factors such as climate extremes, rapid unsustainable urbanization, critical biodiversity loss, and scarcities of food, water and energy have accelerated these risks, further compounding vulnerabilities introduced by conflict and internally displaced and refugee populations, who already suffer from an absence of basic resiliency necessities such as shelter, food and a minimal income security. [13]

Figure 2 - Resilience dimensions

Source: Ryan & Campbell, Comprehensive Crisis Management for Security Practitioners: Structures, Systems and Policies

The United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNISDR) describes key aspects of resilience in its publication How to Make Cities more Resilient – A Handbook for Local Government Leaders. In addition to promoting strong leadership, clear coordination structure and delineated responsibilities, the features of resilience include:

|

Feature

|

Dimension

|

|

Well-defined policies and strategies, including stakeholder engagement and effective communication

|

Crises management; community linkage

|

|

Routinely conducted risk assessments are required to improve knowledge about hazards to inform decisions on planning, development and investment

|

Threats and vulnerabilities

|

|

Financial plan that complements and promotes resilience activities

|

Crises management

|

|

Planning uses up-to-date risk information with a focus on the most vulnerable groups

|

Community linkage

|

|

Building regulations are realistic, compliant and enforced

|

Crises management; community linkage; present and absent resources threats

|

|

Ecosystems are identified, protected and monitored to sustain their function as a natural buffer

|

Crises management; community linkage; threats and vulnerabilities

|

|

Institutions relevant to resilience (for example, health services, transport infrastructure, electrical grid, water quality, sanitation systems and universities) have the capabilities to fulfil their functions

|

Crises management; community linkage; present and absent resources threats and vulnerabilities

|

|

Social connectedness and a culture of help nurtured and strengthened through education, events and communication through multi-media channels

|

Crises management; community linkage;

|

|

Strategies in-place to protect, maintain and upgrade critical infrastructure to ensure services can continue before, during and after a crisis

|

Crises management; present and absent resources

|

|

Preparedness plans, including early warning systems and public preparedness exercises, in-place to ensure an effective response and recovery

|

Crises management

|

|

Recovery strategies aligned with long-term planning

|

Crises management; community linkage; present and absent resources

|

Benefits for the Security Sector?

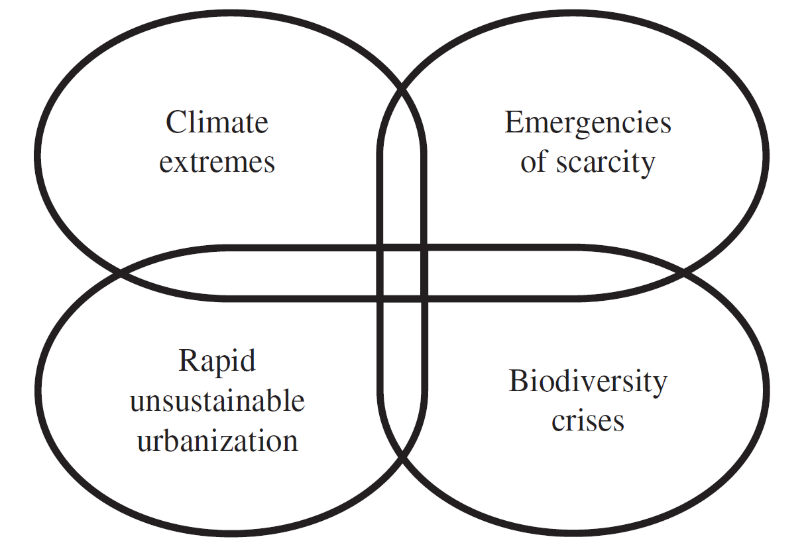

The security sector includes the structures, institutions and personnel responsible for the management, provision and oversight of security such as defense, law enforcement, corrections, intelligence services and institutions responsible for border management, customs and civil emergencies.[14] This sector must consider the broader benefits wherein crisis resilience builds and sustains political, economic and social stability. This includes understanding the relationship between ecosystem and built environment stressors and security sector risks (Figure 3). For example, deforestation or wildfire increases susceptibility to flash flooding and landslides and reduce the carrying capacity for game. Thus, deprived (and often inadequately insured) communities lose gardens and hunting grounds, and may not be able to rebuild their homes and businesses after a major storm or earthquake. [15] Environmental degradation caused by growing populations with little infrastructure support, no external income and few alternative energy options can lead to increased crisis risk for areas that depend on surrounding and distant ecosystems.[16] For these reasons, security sector resilience should consider climate extremes and changes to the environment, rapid unsustainable urbanization and population displacement (especially undocumented populations in urban slums and refugee camps), emergencies of scarcity and food security (water, food, arable land, natural resources), and biodiversity crises (extinctions, protected reserves, ecosystem health).[17]

These stressors in Figure 3 are not direct drivers of crises but risk multipliers that reinforce and exacerbate existing political, socioeconomic tensions and vulnerabilities that destabilize and undermine crisis resilience.[18] Where adaptation to these stressors is ineffective, populations will become displaced as they leave for more habitable environments. Such migration often triggers conflict with other communities as competition for dwindling resources escalates.[19] For example, the Syrian drought from 2007 to 2010 helped fuel the Syrian civil war. Widespread crop failure and unemployment caused mass displacement and migration to economically depressed cities, which could not sustain the burden.[20] The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) highlighted a similar causal link in its 2007 report, “Sudan: Post-conflict Environmental Assessment.” Without resilience, such causal links will become worse as we move into a future characterized by a rapidly increasing global population competing for dwindling resources.

The concept of resilience increases the ability of the security sector to prioritize resources and economic stimulus to those most in need before, during and after a crisis. For example, it creates an understanding of community needs and capacities, strengthens relationships with communities, and provides better partnering and coordination with the full spectrum of volunteers and society.[21] The benefits of this collaborative approach were realized after the Nepal earthquake response when community groups with a relevant work history and experience were more effective in aid distribution than inexperienced international actors.[22] Furthermore, every US$1 invested in preparedness not only saves lives, but can save US$4 in relief and reconstruction costs after a disaster, so resilience is a result of improved economic awareness on the part of those responsible for prioritizing funding streams.[23]

Figure 3 - Current and Future Crisis Risks-ecosystem and built environment stressors

Source: Deon Canyon, Frederick M. Burkle & Rick Speare, “Managing Community Resilience to Climate Extremes, Rapid Unsustainable Urbanization, Emergencies of Scarcity, and Biodiversity Crises by use of a Disaster Risk Reduction Bank,” pp. 1-6.

Why Engage at the Local Level?

he local level is where experiences and perceptions can be drawn on to identify the requirements for effective preparedness, response, recovery and adaptation. Crisis and disaster risk reduction begins and ends at the local level where impacts manifest. [24] Local governments in risk-prone areas, including business and informal settlements, become more resilient through empowerment and ownership if engaged to assist in the identification of priorities, risk factors and vulnerabilities. The Indian National Disaster Management has put this concept into action by partnering with Facebook. It provides disaster responders access to maps of affected areas and gets real-time information to people while providing feedback from those affected through local disaster information volunteers.[25]

All levels of government including the security sector need to engage with their communities to improve resilience.

Inclusion of all members of society at a local level is a key requirement for effective resilience. Without this, vulnerable groups with special needs, such as persons with disabilities, may be overlooked.[26] An online survey conducted by UNISDR in 2013, involving more than 5,000 people with disabilities from 137 countries, found 10% of respondents believe their local government has emergency, disaster management or risk reduction plans that address their access and functional needs, and 20% reported they can independently evacuate immediately without difficulty in the event of a sudden disaster. Also, 51% of respondents expressed a desire to participate in community disaster risk reduction processes.[27]

Investing in resilience at the local level enhances community spirit, improves economic and social well-being, and fosters greater trust in government from the public and private sectors. This includes: strengthened trust in political structures; reduction in fatalities, serious injuries and property damage; active community participation; protection of assets and cultural heritage; increased investment in infrastructure; business opportunities, as well-governed communities attract investment; and balanced ecosystems to increase availability of fresh water, reduce pollution and food security. [28]

How to Build and Sustain Resilience?

To build and sustain resilience, a community must have the ability to self-organize and mobilize available resources during and after a crisis.[29] This requires interdisciplinary collaboration, which includes amalgamation of organizations beyond the traditional disaster and crisis management system (government agency focus) to allow educational, community and private organizations such as universities, primary health care sector (general practitioners and pharmacies) and transport companies to help manage the problem.[30] Using interdisciplinary collaboration, the economic and security sectors can lead articulation and operational discussions on the need to achieve crisis resilience to governmental decision makers, the community, businesses and non-government organizations. For example, after the Indian Ocean tsunami in 2004, the level of devastation in Aceh Province, Indonesia extended well beyond the capacity of the disaster management agency. This led to the creation of a rehabilitation and reconstruction agency that formed partnerships between communities, the private sector and local authorities to allow all stakeholders to be involved in the recovery process. This approach greatly improved coordination and accelerated the reconstruction process.[31]

Effective resilience requires strong ecosystems and built environments, such as health services, transport infrastructure, the electrical grid, water quality, sanitation systems and other municipal utilities required to protect and preserve the health and well-being of communities.[32] Social support systems such as neighborhoods, family and kinship networks, social cohesion, mutual interest groups and mutual self-help groups are important for building resilience.[33] To mitigate this risk, all levels of government including the security sector need to engage with their communities to improve resilience.

An increasingly common methodology used to build resilience is the UNISDR’s “Ten Essentials for Making Cities Resilient.” Although focused on cities, this approach is relevant at the local government level because it covers many common issues that need to be addressed to improve resilience. In Table 1 below, Essentials 1-3 cover governance and financial capacity; 4-8 cover the dimensions of planning and disaster preparation; and 9-10 cover the disaster response and post-event recovery.

Table 1 – The Ten Essentials for Making Cities Resilient

| Essential |

Activities |

| 1. Organize for disaster resilience |

Put in place an organizational structure with strong leadership and clarity of coordination and responsibilities. Establish Disaster Risk Reduction as a key consideration throughout the City Vision or Strategic Plan. |

| 2. Identify, understand, and use current and future risk scenarios |

Maintain up-to-date data on hazards and vulnerabilities. Prepare risk assessments based on participatory processes and use these as the basis for urban development of the city and its long-term planning goals. |

| 3. Strengthen financial capacity for resilience |

Prepare a financial plan by understanding and assessing the significant economic impacts of disasters. Identify and develop financial mechanisms to support resilience activities. |

| 4. Pursue resilient urban development and design. |

Carry out risk-informed urban planning and development based on up-to-date risk assessments with particular focus on vulnerable populations. Apply and enforce realistic, risk compliant building regulations. |

| 5. Safeguard natural buffers to enhance the protective functions offered by natural ecosystems |

Identify, protect and monitor natural ecosystems within and outside the city geography and enhance their use for risk reduction. |

| 6. Strengthen institutional capacity for resilience |

Understand institutional capacity for risk reduction including those of governmental organizations; private sector; academia, professional and civil society organizations, to help detect and strengthen gaps in resilience capacity. |

| 7. Understand and strengthen societal capacity for resilience |

Identify and strengthen social connectedness and culture of mutual help through community and government initiatives and multimedia channels of communication. |

| 8. Increase infrastructure resilience |

Develop a strategy for the protection, update and maintenance of critical infrastructure. Develop risk mitigating infrastructure where needed. |

| 9. Ensure effective preparedness and disaster response |

Create and regularly update preparedness plans, connect with early warning systems and increase emergency and management capacities. After any disaster, ensure that the needs of the affected population sit at the center of reconstruction, with support for them and their community organizations to design and help implement responses, including rebuilding homes and livelihoods. |

| 10. Expedite recovery and build back better |

Establish post-disaster recovery, rehabilitation, and reconstruction strategies that align with long-term planning and providing an improved city environment. |

Source: UNISDR, Disaster Resilience Scorecard for Cities (Geneva: United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction,2017).

To drive action, UNISDR developed a “Disaster Resilience Scorecard for Cities” based on the “Ten Essentials for Making Cities Resilient”. This scorecard provides an assessment that allows local governments to monitor and review progress and challenges in the implementation of the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction – 2015-2030, and assess their level of disaster resilience. The guide shows how to achieve optimal resilience, and challenges complacency by reminding authorities and stakeholders that there is always more to be done to build and sustain resilience.[34] Essentials 1 to 3 are intended to be accomplished first, while the remaining essentials may be completed in any order. Scoring occurs at two levels:

Level 1: Preliminary level, responding to key Sendai Framework targets and indicators, and with some critical sub-questions. This approach is for use in a 1 to 2 day city multi-stakeholder workshop. In total there are 47 questions indicators, each with a 0 to 3 score.

Level 2: Detailed assessment. This approach is a multi-stakeholder exercise that may take 1 to 4 months and can be a basis for a detailed city resilience action plan. The detailed assessment includes 117 indicator criteria, each with a score of 0 to 5.

Recommendations to Enhance Political, Economic and Social Stability

Ι. Security Sector Scorecard

A security sector resilience scorecard should be developed to provide a mechanism for measuring stability. The UNISDR’s “Ten Essentials for Making Cities Resilient” provides a template for developing such a scorecard. Thematical areas of focus could include the underlying risk drivers of societal collapse from a crisis such as poverty and inequality, poor living conditions, unplanned urbanization processes, ecosystem and built environment stressors, and lack of regulations and enforcement.[35]

Development of the scorecard should be led by a team of multi-disciplinary security experts and crisis scholars with experience in the Indo-Pacific. This would enable the region to better prepare for and respond to crises by helping to understand the risk of disasters and the need for political, economic and social resilience. Multi-sectoral participation, including private sector partnerships, will improve collaboration on crisis preparedness issues and strengthen regional capacity to mitigate, prepare, respond and recover from crises.

Completion of the scorecard should be led by local governments with support from security experts, non-government organizations, community members and provincial, national government and regional agencies. It could be mandated at local, provincial and/or national levels through legislation, financial incentives or regional agreements. If developed and implemented, a community-focused scorecard aggregated across local, provincial, national and regional levels would provide a systems-based approach to understanding security sector risks and priority areas for enhancing resilience across the Indo-Pacific.

Ⅱ. Cluster Approach to Resilience and Stability

A cluster approach to resilience is recommended to systematize the management of building and sustaining political, economic and social stability. This concept derives from the U.N. Cluster Approach to humanitarian and disaster response, which includes U.N. and non-UN organizations that focus on different sectors of humanitarian action (e.g. water, health and logistics) during the time of a disaster or crisis.[36] Adoption of this type of proven and field-tested approach would provide a well-rounded mechanism and decision-making tool for enhancing political, economic and social resilience.

If resilience is weak or does not exist, a crisis acts as a negative multiplier that reinforces and exacerbates existing political, socioeconomic tensions.

Due to the range of disciplines involved in achieving resilience, development and implementation of a “Cluster Approach to Resilience and Stability” will require collaborative governance.[38] This would start with multi-disciplinary security experts and crisis scholars articulating the need to measure, build and sustain political, economic and social resilience (incentive to participate).[39] The next steps would be: face-to-face discussions; trust building to develop a shared understanding; engaging in comprehensive and shared planning; pooling and jointly acquiring resources; and achieving intermediate outcomes such as agreeing on the need for resilience. Through this approach an open, inclusive and constructive dialogue would occur, to create shared values for achieving resilience.[40] This will provide the foundation for a well-rounded decision-making framework to develop a “Cluster Approach to Resilience and Stability” that builds and sustains political, economic and social stability across the Indo-Pacific.

Conclusion

Crisis resilience has a critical role in building and sustaining political, economic and social stability across the Indo-Pacific. This must be understood by the security sector due to the increasing complexity, and the often multidisciplinary and transboundary nature, of modern-day crises. If resilience is weak or does not exist, a crisis acts as a negative multiplier that reinforces and exacerbates existing political, socioeconomic tensions and vulnerabilities that can have a destabilizing affect and result in societal collapse. To prevent this from occurring, a security sector resilience scorecard must be developed to measure and help build and sustain stability. Implementation would enable the region to better prepare for and respond to crises by helping to understand risks and identify priority areas for action. This scorecard would need to be complemented by a Cluster Approach to Resilience and Stability to systematize the management of building and sustaining political, economic and social stability. Achieving this will provide a well-rounded and systems-based approach to enhancing local, provincial and national level crisis resilience and stability across the Indo-Pacific.

(The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Daniel K. Inouye Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.)

Dr Benjamin J. Ryan is an Associate Professor of Daniel K. Inouye Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies, Honolulu HI, USA. Dr. Deon V. Canyon and Dr. James Campbell are Professors of Daniel K. Inouye Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies. Dr. Frederick M. Burkle, Jr. is a Senior HHI Fellow of Harvard Humanitarian Initiative, Visiting Scientist of Harvard School of Public Health, and Professor of the Department of Community Emergency Health of Monash University Medical School. Dr. Wie-Sen Li is an Executive Secretary of the National Science and Technology Center for Disaster Reduction, Taiwan.

[1]UNISDR, Disaster Resilience Scorecard for Cities (Geneva: United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, 2017); UNISDR, How to Make Cities More Resilient - A Handbook for Local Government Leaders (Geneva: United Nations, 2017).

[2]Frederick M. Burkle, Shinichi Eqawa, Anthony G. MacIntyre, Yasuhiro Otomo, Charles W. Beadling & John T. Walsh, “The 2015 Hyogo Framework for Action: Cautious Optimism,” Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, Vol. 8, Issue.3(2014), pp.191-192.

[3] Frederick M. Burkle, “Hyogo Declaration and the cultural map of the world,” Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, Vol. 8, No.4(2014), 280-282.

[4]UNISDR, Disaster Resilience Scorecard for Cities; UNISDR, How to Make Cities More Resilient - A Handbook for Local Government Leaders.

[5]Peter Roders, “Development of resilient Australia: enhancing the PPRR approach with anticipation, assessment and registration of risks,” The Australian Journal of Emergency Management, Vol. 26 (2011), pp. 56-58.

[6]UNISDR, Implementation guide for local disaster risk reduction and resilience strategies - Public consultation version (Geneva: United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, 2018).

[7]“Terminology,” UNISDR, Retrieved December 27, 2017, from http://www.unisdr.org/we/inform/terminology#letter-r

[8]Ibid.

[9] UNISDR, Disaster Resilience Scorecard for Cities; UNISDR, How to Make Cities More Resilient - A Handbook for Local Government Leaders.

[10]Ibid.

[11]“Resilience,” UN-Habitat, Retrieved December 27, 2017, from https://unhabitat.org/urban-themes/resilience/

[12] UNISDR, Disaster Resilience Scorecard for Cities; UNISDR, How to Make Cities More Resilient - A Handbook for Local Government Leaders.

[13]Frederick M. Burkle, “Current Crises & Potential Conflicts in Asia and the Pacific Health by a Different Name,” Presented at the “Institutional Coordination in Disaster Management in the Asia Pacific” Conference 9 -10 April 2018, University of California at Berkeley APEC Study Center & the University of California San Diego Medical School.

[14] United Nations, “Security Sector Reform,” Retrieved September 24, 2018, from https://peacekeeping.un.org/en/security-sector-reform

[15]UNISDR, Disaster Resilience Scorecard for Cities; UNISDR, How to Make Cities More Resilient - A Handbook for Local Government Leaders.

[16] Ibid.

[17]Deon Canyon, Frederick M. Burkle & Rick Speare, “Managing Community Resilience to Climate Extremes, Rapid Unsustainable Urbanization, Emergencies of Scarcity, and Biodiversity Crises by use of a Disaster Risk Reduction Bank,” Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, Vol. 9, No. 6(2015), pp. 1-6.

[18]Onita Das, “Climate change and armed conflict: Challenges and opportunities for maintaining international peace and security through climate justice,” In R. Abate, Climate Justice: Case Studies in Global and Regional Governance Challenges (Washington D.C.: Environmental Law Institute, 2016). Retrieved from http://eprints.uwe.ac.uk/30412; Deon Canyon, Frederick M. Burkle & Rick Speare, “Managing Community Resilience to Climate Extremes, Rapid Unsustainable Urbanization, Emergencies of Scarcity, and Biodiversity Crises by Use of a Disaster Risk Reduction Bank.”

[19]Onita Das, “Climate change and armed conflict: Challenges and opportunities for maintaining international peace and security through climate justice.”

[20] Ibid.

[21] U.K. Government, “The context for community resilience,” 2016, October 26, Retrieved December 28, 2017, from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/community-resilience-framework-for-practitioners/the-context-for-community-resilience#the-benefits-of-resilient-individuals-businesses-and-communities

[22]Alistair Cook, Maxim Shrestha & Zin Bo Htet, The 2015 Nepal Earthquake: Implications for Future International Relief Efforts (Singapore: RSIS Centre for Non-Traditional Security Studies, 2016).

[23]Multihazard Mitigation Council, Natural Hazard Mitigation Saves: An Independent Study to Assess the Future Savings From Mitigation Activities - Volume 1: Findings, Conclusions, and Recommendations (Washington DC: National Institute of Building Sciences, 2005).

[24]Deon Canyon, Frederick M. Burkle & Rick Speare, “Managing Community Resilience to Climate Extremes, Rapid Unsustainable Urbanization, Emergencies of Scarcity, and Biodiversity Crises by Use of a Disaster Risk Reduction Bank.”

[25]NDMA, “PRESS RELEASE Kiren Rijiju inaugurates NDMA's India Disaster Response Summit,” National Informatics Centre, November 9, 2017, Retrieved from http://pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=173344

[26] Marita Vos & Helen Sullivan, “Community Resilience in Crises: Technology and Social Media Enablers,” Human Technology: An Interdisciplinary Journal on Humans in ICT Environments, Vol. 10, No. 2(2014), pp. 61-67.

[27]UNISDR, Disaster Resilience Scorecard for Cities; UNISDR, How to Make Cities More Resilient - A Handbook for Local Government Leaders.

[28] Ibid.

[29]Marita Vos & Helen Sullivan, “Community Resilience in Crises: Technology and Social Media Enablers.”

[30]Benjamin J. Ryan, Richard C. Franklin, Frederick M. Burkle, Erin C. Smith, Peter Aitken, Kerrianne Watt, Peter A. Leggat, “Ranking and prioritizing strategies for reducing mortality and morbidity from noncommunicable diseases post disaster: An Australian perspective,” International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, Vol, 27 (2018), pp. 223-238.

[31]UNISDR, Disaster Resilience Scorecard for Cities; UNISDR, How to Make Cities More Resilient - A Handbook for Local Government Leaders.

[32]Deon Canyon, Frederick M. Burkle & Rick Speare, “Managing Community Resilience to Climate Extremes, Rapid Unsustainable Urbanization, Emergencies of Scarcity, and Biodiversity Crises by Use of a Disaster Risk Reduction Bank.”

[33]Paul Arbon, Lynette Cusack, Kristine Gebbie, Malinda Steenkamp & Olga Anikeeva, How do we measure and building reslience against disaster in communities and households (Adelaide, Australia: Torrens Resilience Institute, 2013).

[34]UNISDR, Disaster Resilience Scorecard for Cities; UNISDR, How to Make Cities More Resilient - A Handbook for Local Government Leaders.

[35]UNISDR, Implementation guide for local disaster risk reduction and resilience strategies - Public consultation version (Geneva: United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, 2018).

[36]OCHA, “Cluster Coordination,” United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, May 10, 2018, Retrieved from http://www.unocha.org/legacy/what-we-do/coordination-tools/cluster-coordination

[37]Janine O'Flynn & John Wanna, Collaborative Governance: A new era of public policy in Australia? (Canberra: ANU Press, 2008); Benjamin Ryan et al. “Ranking and prioritizing strategies for reducing mortality and morbidity from noncommunicable diseases post disaster: An Australian perspective.”

[38] Chris Ansell & Alison Gash, “Collaborative governance in theory and practice,” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, Vol. 18, No. 4 (2008), pp. 543-571; John Donahue, “On Collaborative Governance,” Corporate Social Responsibility Initiative Working Paper No.2 (Cambridge, MA: John Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, 2004).

[39]Ibid.