An Emerging Island Chain within the Island Chains

2020.12.22

Views

582

By Jung-Ming Chang[1]

Introduction

After Liu Huaqing, former admiral of the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) of the People’s Republic of China (PRC)proposed in 1982 his version of naval strategy for China, the PRC has been constructing a blue navy. As Alfred Thayer Mahan [2]points out the importance of military bases to a blue water navy, seeking and turning foreign ports into military use has become China’s priority. Therefore, China established ties with countries in the South Pacific in order to conduct a breakthrough of the three island chains set up by the United States during the Cold War. These island states, then, constitute an emerging island chain. To prevent a military confrontation, or even a war, from occurring in the region, looking squarely into the emerging island chain within the island chains is necessary.

An Emerging Island Chain and Its Significance

The world has recently witnessed an expansion of China’s influence in the South Pacific, a region that has long been mostly under the influence of the United States, Australia, and New Zealand. The switch of diplomatic recognition from Taiwan to China by the Solomon Islands and Kiribati in September 2019 served as two examples of the rise of China’s influence in the region.[3] More importantly, Honiara switched diplomatic ties to Beijing after resisting Washington’s opposition. Therefore, the switch was not a simple move of changing partners. It was, in fact, a behind-the-scenes competition between China and the United States.

Establishing ties with countries in the South Pacific not only extends China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) but also brings the nation tremendous strategic advantages. Directly after the diplomatic switch, China’s state-owned Sam Enterprise signed a lease with the Solomon Islands’ Central Province to rent Tulagi Island for 99 years. The attempt was later rebuked by the Attorney General’s Chambers of the Solomon Islands, stating that the signing was illegal and should be terminated immediately.[4] China’s second attempt was to provide economic assistance to improve roads and railroads in Guadalcanal, a transportation hub and bloody battlefield during World War II, to facilitate the reopening of the Gold Ridge Mine on the island.[5] What should not be overlooked is that both attempts indicate China’s intentions to seek strategically located allies in the South Pacific.

The idea of using island chains to prevent the spread of communism from USSR was proposed in the early days of the Cold War, and over the years, this idea has evolved further. The First Island Chain starts from Japan and extends southbound to Ryukyu Islands, Taiwan, the Philippines, and Malaysia. The Second Island Chain comprises Japan, the Ogasawara Islands, the Mariana Islands, Guam, Palau, and Indonesia, with a view to intercepting the remaining communist forces. Alaska, the Aleutian Islands, Midway Atoll, Hawaii, the Line Islands (partly controlled by Kiribati), and New Zealand form the Third Island Chain that constitutes the last line of defense that deters adversarial forces from reaching the U.S. continent.

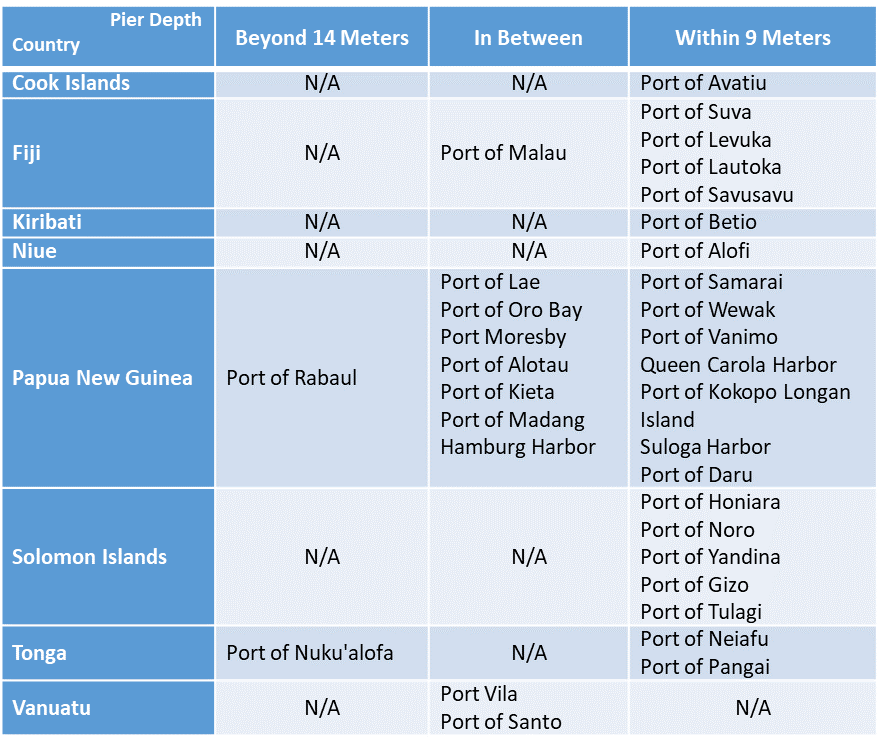

An emerging island chain that starts from Papua New Guinea and ends in Kiribati, however, is located within the Second and Third Island Chains and has shown support to China. More importantly, countries in the emerging island chain have existing commercial ports that could be turned into military use. Port of Rabaul (Papua New Guinea) and Port of Nuku’alofa (Tonga) both have a pier depth of more than 14 meters and could accommodate almost any vessel in the world, commercial or military ones. A pier that is at least 9 meters in depth could dock most of the PLAN vessels and there is one port of this kind in Fiji, seven in Papua New Guinea, and two in Vanuatu. For more information, please see Table 1. Even if the rest of the existing commercial ports do not have adequate pier depth, China would not mind to conduct some construction projects in exchange for free use of these ports.

After greatly enhancing its national capabilities, China certainly desires to reach out to the Pacific and penetrate the three Island Chains. If deployed deliberatively, China’s capability of Anti-Access/Area Denial (A2/AD) could be extended by 3,000 miles. Therefore, the strategic importance of the emerging island chain should not be overlooked.

A Possible Extension of China’s Anti-Access/Area Denial Weapon System

Originally, the A2/AD strategy was established by China after the 1995–96 missile crisis to prevent U.S. forces from coming to Taiwan’s aid again. During the crisis, the U.S. government deployed two aircraft carrier battle groups to obstruct the Chinese communists from taking any military actions in addition to test-firing missiles to influence Taiwan’s presidential election. USS Independence aircraft carrier combat group embarked from Yokosuka, Japan to an area near northern Taiwan; a combat group led by Nimitz-class aircraft carrier that traveled from the Arabian Gulf to south of Taiwan.

Seeing how the PLAN was no match for the military prowess of the U.S. aircraft carriers, the strategy of preventing the U.S. forces from reaching international waters near Taiwan in the future was conceived. To this end, long-range Dongfeng-21D (DF-21D) ballistic missiles were developed and dubbed “carrier killers.” Additionally, mid-range Dongfeng-26 (DF-26) ballistic missiles, nicknamed the Guam Express, were added to China’s Rocket Force in 2018. Recently, China has developed a type of hypersonic glide missile, the Dongfeng-17 (DF-17), which can strike targets at a speed of Mach five.

Following China’s strengthening of its naval force, the PLAN could deploy vessels in the East China Sea in advance to deny access to the U.S. warships coming from Japan. Similarly, China’s recent construction and fortification in the Spratly Islands also poses a direct threat to any U.S. combat group traversing the South China Sea. To some extent, China’s air force and land-based batteries are capable of impeding the movement of U.S. vessels in these regions.

After the PLAN conducting long voyages through the Miyako Pass, its vessels have had the ability to stymie U.S. vessels rushing to the First Island Chain. To bring a quick end to the combat, China has devised tactics, such as ensuring that the first battle is the decisive one. Hence, any delay in the U.S. rescue mission increases China’s likelihood of success in blitzkrieg warfare. Currently, the PLAN has two Kuznetsov-class aircraft carriers, Liaoning (CV16) and Shandong (CV17), and two more carriers will join the fleet in the near future.

Three aircraft carriers constitute a reliable force; one of each can be assigned for active duty, training, and repair and maintenance. With three aircraft carriers at its disposal and after securing deep-water ports in the emerging island chain, the PLAN could well deploy these carriers to the South Pacific. Because the current and upcoming PLAN aircraft carriers are powered by steam turbines, their fuel tank capacity limits the voyage duration to 7 days. However, considering the length between Guam and Honiara, a PLAN combat group comprising one aircraft carrier and escort vessels can feasibly make one roundtrip within a week. For voyages further north, an auxiliary oiler replenishment ship can be used.

Moreover, the PLAN fleet in the South Pacific is likely to be accompanied by submarines and unmanned underwater vessels (UUVs), thereby posing a considerable potential threat to the U.S. fleets. The PLAN submarines and the JL-class ballistic missiles on board are grave concerns for the U.S. Navy. To deceive the U.S. Navy, the PLAN could have its supply vessels sauntering in the middle of the North Pacific Ocean to give the impression that the PLAN submarines are on active duty nearby.

Additionally, the PLAN can deploy SHU001 UUVs, which were unveiled on the People’s Republic of China’s National Day in 2019. Unlike PLAN aircraft carriers that are constrained by short refueling cycles, UUVs are powered by batteries and can be operational for at least 30 days. These unmanned vessels can not only detect U.S. fleets but plant mines. Additionally, if China’s HSU001 is proven to be reliable in terms of intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance, the military prowess of DF-17s and DF-21Ds could be greatly enhanced.

Confronting or disturbing the U.S. fleets will be possible for the PLAN vessels if they are stationed on the emerging island chain. Additionally, they can be used to limit the reach of the U.S. Navy. In the occasion that a PLAN task force fails to deter a U.S. fleet rushing to the aid of countries in the First Island Chain, it could follow the U.S. fleet and strike from behind. In this case, the U.S. fleet may need to engage on both fronts (front and back).

One could argue that for a Chinese military base to exercise its maximum military power in the emerging island chain, defense is of utmost concern for China. In other words, China must be able to protect its military compound in the South Pacific before using it as a forward outpost. However, no military base in modern warfare is absolutely safe; hence, focusing on defense capabilities is less critical. Even if U.S. forces conduct a preventive strike, defeating all PLAN aircraft carriers, surface ships, submarines, and UUVs in a single military action would be almost impossible as some of them would still be operational. Additionally, one could argue that the United States, with the support of its allies, could deploy military forces in advance to prevent PLAN vessels from leaving base in the South Pacific. However, this argument is void because no legal solution is available to prevent a PLAN fleet from enjoying the freedom of navigation.

Other strategies have been proposed to counter China, such as preventing the PLAN from making inroads into the First Island Chain during wartime by deploying a multi-domain task force or developing land-based missiles to safeguard the choke points. The First Island Chain remains the central focus, despite the knowledge that the PLAN can deploy aircraft carriers and escort vessels in the South Pacific in advance before the onset of war.

Military Versus Diplomatic Solutions

Aware of the situation, the Australian and U.S. governments have started making military preparations. For example, the Australian government is planning to construct a naval base at Glyde Point in Australia’s Northern Territory, which will be used by U.S. Marines.[6] Moreover, the Lombrum naval base on Manus Island of Papua New Guinea has been under development since 2018 as a joint effort by the United States and Australia.[7]

Besides, Palau President Tommy Remengesau urged the United States to build military bases in his country during U.S. Secretary of Defense Mark Esper’s visit to the archipelago in late August 2020. Additionally, the U.S. Department of Defense has proposed building a fleet of 355 vessels by 2030 at an average annual cost of US$26.6 billion (2017 currency rate) per year over the next 30 years.[9] However, consider inflation and the declining U.S. economy, whether the goal can be reached in a timely fashion is debatable.

All the aforementioned problems stem from the Chinese government’s possible control over the ports in the emerging island chain. In other words, if the PLAN does not touch the ports, regional countries can rest assured that the South Pacific would remain as peaceful as always. Since the military perspectives previously mentioned have been inefficient in resolving this issue, diplomatic means that are both time and budget efficient must be proposed.

Strengthening economic ties with countries in the South Pacific is a strategic objective of China’s BRI. Moreover, the BRI is welcomed by island states in the South Pacific for the economic and infrastructural benefits it promises. Given that the island countries in the South Pacific are generally economically weak, providing free-of-cost infrastructure to these countries is an easy means of exerting influence. Therefore, a counter measure to cope with the BRI must involve financial assistance.

The United States does not need to provide financial assistance alone, but could coordinate with Taiwan, Japan, New Zealand, Australia, or France, to enlarge the funding base. These countries have been providing economic assistance to nations in the South Pacific; therefore, continuing to donate makes sense for them. Additionally, in light of the growing strategic importance of the South Pacific, these donor countries may be willing to donate more than before. To avoid a war with China, it is logical for the U.S. government to take the lead in rallying donor countries to better gauge the needs of recipient countries.

Two such collaborative projects are currently operational: The Global Cooperation and Training Framework and Pacific Islands Dialogue between the United States and Taiwan. Additionally, ad hoc cooperation is underway to prevent the possible outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic in the South Pacific. As the late Director of the American Institute in Taiwan, Darryl Johnson, said to me in his office 21 years ago, “diplomatic business offers various means to solve problems,” perhaps more could be done in the future to strengthen ties with the South Pacific allies to secure regional stability or even world peace.

Another possible solution is to establish more air traffic routes to connect the South Pacific island states with the outside world. Even though United Airlines, famous for its “island hopper” route from Guam to Honolulu, and a few local airlines have been operating in the region, air travel is still inconvenient for island states that are not on the busy routes. For example, the direct distance from Brisbane, Australia to Majuro of the Marshall Islands is approximately 4,000 miles; however, passengers have to transit through Honolulu; this lack of a direct flight makes the journey 2.6 times longer. Similarly, Palau is located between Taipei and Brisbane. Ideally, a traveler from Taipei should be able to visit Palau first and then Brisbane second; however, because no direct flights exist between Palau and Brisbane, a traveler has to return to Taipei after visiting Palau and fly to Brisbane from Taipei instead. Many such cases of poor air connectivity can be cited. It is necessary to enhance the convenience of transportation to create a stronger bond between South Pacific island states and other countries in the region.

Conclusion

China has been attempting to establish an emerging island chain in the South Pacific to expand its influence. Utilizing the maintenance and supply provided by the ports of this emerging island chain could easily turn it into a forward military base, which would devastate regional security or even world peace. To start a war with the United States might not occur in the near future, but to “liberate Taiwan” could be imminent. It is necessary to tackle this issue before China strengthens its beachhead in the South Pacific. When choosing which actions to take, diplomatic means are time and budget efficient than military means.

Table 1: Ports in the Emerging Island Chain

Sources: World Port Source, available at http://worldportsource.com/; World Seaports Catalogue, Marine and Seaports Marketplace, available at http://ports.com/.

Jung-Ming Chang is a post-doctoral fellow at the Institute for National Defense and Security Research, Taiwan. He holds a Ph.D. degree in Government and Politics from University of Maryland. Prior to getting doctoral education, he worked at the Cultural and Information Section of the American Institute in Taiwan.

[1] The author would like to thank Christian Castro, Sifu Ou, Liang-Chih Evans Chen, Kuochou Peng (ROC Navy Rear Admiral), Hsinbiao Jiang (ROC Navy Captain, retired) and Grant Newsham (US Marine Colonel, retired) for helpful comments. All errors are of course mine.

[2]Alfred Thayer Mahan, Naval Strategy: Compared and Contrasted with the Principles and Practice of Military Operations on Land. (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1911), pp. 200-201.

[3] Chris Horton, “In Blow to Taiwan, Solomon Islands Is Said to Switch Relations to China,” The New York Times, September 16, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/16/world/asia/solomon-islands-taiwan-china.html; Melissa Clarke, “Kiribati cuts ties with Taiwan to switch to China, days after Solomon Islands,” ABC News, September 20, 2019, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-09-20/kiribati-to-switch-diplomatic-ties-from-taiwan-to-china/11532192.

[4]Neal Conan, “Pacific News Minute: Chinese Bid to Lease Tulagi Island Fails,” Hawai’i Public Radio, October 30, 2019, https://www.hawaiipublicradio.org/post/pacific-news-minute-chinese-bid-lease-tulagi-island-fails#stream/0.

[5]“Gold Ridge gold mine relaunched in Solomon Islands,” Radio New Zealand, October 26, 2019, https://www.rnz.co.nz/international/pacific-news/401844/gold-ridge-gold-mine-relaunched-in-solomon-islands.

[6]Andrew Greene, “Secret plans for new port outside Darwin to accommodate visiting US Marines,” ABC News, June 19, 2019, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-06-23/navy-port-us-darwin-glyde-point-gunn-marines-gunn-military/11222606.

[7]“PNG to review deal with Australia for naval base on Manus,” Radio New Zealand, June 12, 2020, https://www.rnz.co.nz/international/pacific-news/418860/png-to-review-deal-with-australia-for-naval-base-on-manus.

[8]“Palau invites US to build military bases as part of strategic tug of war with China,” South China Morning Post, September 4, 2020, https://www.scmp.com/news/asia/australasia/article/3100244/palau-invites-us-build-military-bases-part-strategic-tug-war.

[9]“Costs of Building a 355-Ship Navy,” Congressional Budget Office, April 24, 2017, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/52632.