China’s Cyber Corps and Strategies

2018.10.01

Views

11230

By Si-Fu Ou

Today’s fight in cyberspace occurs in the gray zone between war and peace. Chinese state-sponsored hackers have focused largely on the theft of intellectual property, trade secrets, and other sensitive commercial information. Its chief aim has been to boost Chinese economic competition. More recently, however, China shifts its hackers from industrial spies to cyber warriors. The Chinese seem focused on gleaning intelligence on military capabilities and on government officials who interact with defense contractors. China has emphasized the importance of cyberspace as a new domain of national security and an arena for strategic competition. China’s leadership continues to direct the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to be capable of fighting and winning local wars under informationized conditions. China has taken a leadership role among the top cyber powers, now openly declaring its place with the US, Russia and other countries. In order to understand the Chinese cyber threats, one has to explore the PLA cyber forces and its related strategies.

China’s Cyber Corps

It is first important to understand gulfs in how China and the US define cybersecurity/network security and other related terminology. In Chinese literature there currently exists no formal, authoritative terminology for “cyber,” “cybersecurity,” or other terms stemming from the word “cyber,” though the Chinese government and scholars have adapted to its usage in English-language media. Instead, China uses “information security” and “network security” to refer to similar concepts. Western scholars should recognize the differences and implications for each of the terms to include or infer cyber connotations.

The Chinese government, academic, and military literature relevant to the “cyber” domain often refer to “network”-related terminology (網絡). Parallels to English-language terminology include the use of the term “network space” (網絡空間) to refer to “cyberspace” (賽博空間) and the term “cyber operations” parallels the PLA term “network warfare” (網絡戰). The PLA literature currently positions “cyber” concepts within the “information operations” domain (信息作戰), although “information operations” also encompasses a broad range of other concepts in computing, psychological operations, and the electromagnetic spectrum.[1]

The Strategic Support Force’s cyber mission has been given to the Network Systems Department (網絡系統部, or NSD), a deputy theater command leader grade (副戰區級) organization that acts as the headquarters for the SSF’s cyber operations forces, sometimes referred to as a cyber corps or cyberspace operations forces (網軍或網絡空間作戰部隊). Despite its name, the Network Systems Department and its subordinate forces are responsible for information warfare more broadly, with a mission set that includes cyber warfare, electronic warfare, and psychological warfare (311 Base, which conducts information warfare—disinformation and influence activities). At first glance, the Network Systems Department appears to represent a renaming, notional reorganization, and grade promotion of the former Third Department (總參三部, or 3PLA) of the PLA GSD (General Staff Department), which appears to have moved in its entirety. Much as the institutions of the former GSD provided the partial foundation for the creation of the Space Systems Department, but they also form the organizational core of the NSD. The Network Systems Department maintains the former Third Department’s headquarters, location, and internal bureau-centric structure. In at least one instance, the NSD has been referred to as the “SSF Third Department” (戰略支援部隊第三部), mirroring its former appellation.[2]

To foster cyber professionals, China seeks to establish several cybersecurity schools in Chinese universities as training grounds for cyber-warriors.

The cyber responsibilities lie with the GSD’s Third and Fourth Departments that conduct advanced research on information security. The 3rd Department is responsible for signals intelligence and focuses on collection, analysis and exploitation of electronic information. The 4th Department oversees electronic counter-measures and research institutes developing information warfare technologies. The military also maintains ties with research universities and others in the public sector.[3]

To foster cyber professionals, China seeks to establish several cybersecurity schools in Chinese universities as training grounds for cyber-warriors. These schools are Xidian University, Southeast University, Beihang University, Wuhan University, Sichuan University, the University of Science and Technology of China, and the SSF Information Engineering University. One quickly notices two trends. First, the seven schools encompass all regions of China, meaning the search for talent will cover the entire nation of 1.37 billion. Second, the batch is a mixture of civilian and military-affiliated universities. Such a model of civil-military fusion (軍民融合) will help schools complement one another’s limitations.[4]

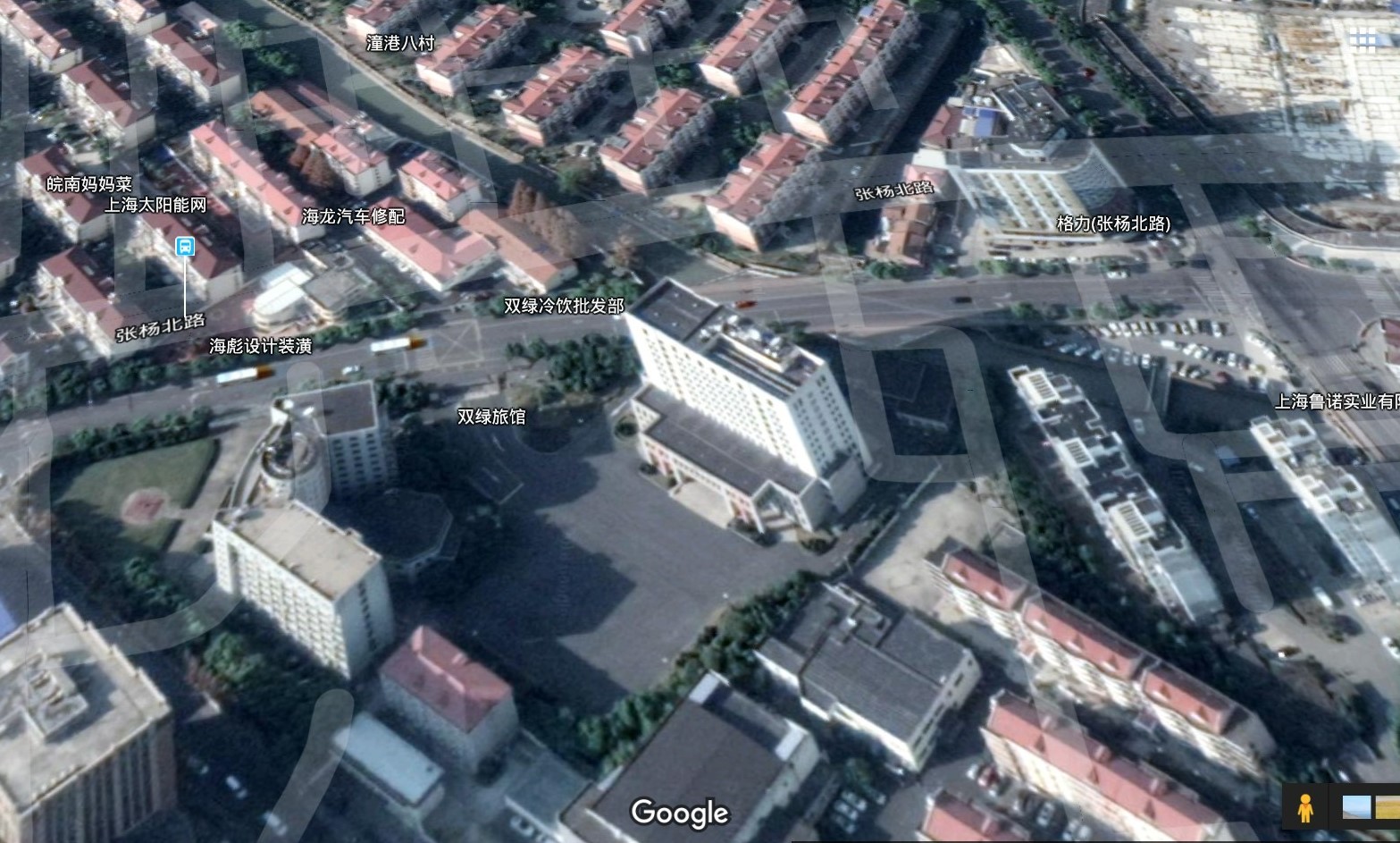

The SSF may represent the PLA’s first step in developing a cyber force that combines cyber reconnaissance, attack and defense capabilities under one hat. Importantly, it appears the PLA has taken note of US Cyber Command’s structure that consolidated cyber functions under a single entity.[5] The China’s Cyber Corps is believed to employ 100,000 hackers, language specialists and analysts at its headquarters in the Haidian District in Beijing. Branch units are located in Shanghai, Qingdao, Sanya, Chengdu and Guangzhou. In May 2014, the US government indicted five midlevel PLA hackers who were part of a Shanghai-based group known as Unit 61398. An NSA document made public by renegade former contractor Edward Snowden revealed that 3PLA’s Technical Department is one of the Chinese government’s most aggressive cybertheft actors, with 19 confirmed and nine other possible cyberunits under its command. The other major cyberspying organization is the Chinese Ministry of State Security (MSS), which runs six known and 22 suspected cyberspying units.[6] The use of 3PLA for economic cyber espionage is part of the policy of civil-military fusion programs that involve China sharing resources between science and technology entities and the PLA.[7]

This white building on Shanghai is the headquarters of Unit 61398 of the PLA. (Source: Google map)

China shifted its hackers from industrial spies to cyber warriors in late 2015. Most countries engage in some sort of espionage of each other’s governments. From 2006 to 2014, China was very active in cyberespionage of commercial interests as opposed to government secrets. Some scholars argue that commercial espionage was as necessary to build the Chinese economy. A massive commercial cyberespionage campaign was made possible, in large part, through direct government support from the military’s Unit 61398. However, by 2017, Unit 61398 was mostly disbanded, as Chinese cyber strategy completed its shift from commercial to government objectives, and from volume to sophistication.[8]

Assessing the strength of the Chinese cyber force, a Rand paper concluded that China’s cyber activities have become a major source of concern in the US and allied countries. There is strong evidence that many of the hostile cyber espionage activities emanating from China are tied to the PLA. The PLA has maintained organized cyber units since at least the late-1990s, while the US Cyber Command was only formed in 2009. Nevertheless, under wartime conditions, the US might not fare as poorly in the cyber domain as many assume. Moreover, in evaluating the likely relative impact of cyber attacks, the target user’s skills, network management, and general resiliency are at least as important as the attacker’s capabilities. In all of these areas, the US enjoys substantial advantages, though Chinese performance is improving. Chinese cyber security is suspect, and its civilian computers suffer from the world’s highest rate of infection by malware. Both sides might nevertheless face significant surprises in the cyber domain during a conflict, and US logistical efforts are particularly vulnerable, since they rely on unclassified networks that are connected to the Internet.[9]

China’s Cyber Warfare Strategies

China’s cyber strategies are evolving in parallel with the PLA ongoing military reforms and modernization drives. Dean Cheng, senior research fellow at the Heritage Foundation's Asian Studies Center, said that “before horses and troops move,” China wants to have information dominance (制信息權) over its rivals. To China, cyber is a distinct subset of information operation.[10] On informationization, Cheng argued further that Chinese leadership views the world as having entered an information age, in which the very nature of international power, the currency of international power, has shifted from traditional industry toward the ability to gather information, analyze information and exploit information. As a result, China believes that, in a sense, the global balance of power has been reset to zero, where everyone is starting from the same starting point, and China can therefore catch up much more easily. On the Chinese perspective on conflict within the context of informationization, Cheng wrote: “the focus of informationized warfare is establishing information dominance. This is the ability to establish control of information and information flow at a particular time and within a particular space.”[11]

China discusses its own emphasis on cyberwar strategies in several official documents. In the 2015 China’s Military Strategy white paper, it declared that “Cyberspace has become a new pillar of economic and social development, and a new domain of national security … As cyberspace weighs more in military security, China will expedite the development of a cyber force, and enhance its capabilities of cyberspace situation awareness, cyber defense, support for the country’s endeavors in cyberspace and participation in international cyber cooperation, so as to stem major cyber crises, ensure national network and information security, and maintain national security and social stability.”[12]

The 2013 edition of the Science of Military Strategy — a study of the PLA’s strategic thinking, published by China’s Academy of Military Sciences—outlines different types of military operations in cyberspace: network reconnaissance, network defense, network attack and network deterrence. The insights it reveals in what appears to be a comprehensive Chinese “whole nation” approach to conducting cyber war. The paper acknowledges that the Ministry of State Security and Ministry of Public Security have also been authorized by the military to carry out network warfare operations. The document also mentions “external entities” outside the public sector that can be organized and mobilized for network warfare operations—a euphemism for the private sector and patriotic hackers. The PLA has opted for a comprehensive whole nation approach when mobilizing for cyber war. This approach may, perhaps more effectively than in western countries, put civilian and non-state actor capabilities in the hands of senior military decision-makers who can more effectively channel and direct these resources for a variety of operations in cyberspace.[13]

Secondly, this highly integrated approach extends to the PLA’s conceptualization of the forces that would participate in cyber operations, which would further blur the conventional distinction between military and civilian domains. Beyond the longstanding linkage of information warfare to the traditional concept of people’s warfare, the Chinese also allude to the participation of civilians in information warfare, observing that the boundaries between military personnel and common people and between civilian-use and military-use technologies have all become indistinct. They directly support the participation of civilian cyber forces in a conflict scenario and argue since military and civilian attacks are hard to distinguish, the PLA should persist in the integration of the military and civilians, such that “in peacetime, civilians hide the military, while in wartime, the military and the people, hands joined, attack together… This intended participation of civilian forces is often linked to the expansive concept of civil-military fusion. Such mobilization of civilian forces is unorthodox relative to most western militaries and could complicate attribution efforts in a crisis through enabling plausible deniability to engage in proscribed cyber activities.[14]

The PLA has opted for a comprehensive whole nation approach when mobilizing for cyber war.

Thirdly, the PLA’s approach to information warfare has been characterized by the concept of “the integration of peace and warfare” (平戰結合) and a corresponding lack of differentiation between civilian and military targets. Cyber attack and defense countermeasures are an everyday occurrence, such that cyber military struggle is underway at all times, including anticipated attacks on civilian targets and critical infrastructure, such as power, transportation, and communications systems. Similarly, the strategic game in cyberspace is not limited by space and time, does not differentiate between peacetime and wartime, and does not have a front line and home-front.

Finally, the PLA’s approach to cyber warfare could translate into a focus on extensive peacetime cyber preparation of the battlefield, which could undermine strategic stability. The PLA appears to take a highly integrated conceptual and likely operational approach to “cyber reconnaissance” (網絡偵查) and cyber attack. That is, for the PLA peacetime cyber reconnaissance (often characterized as cyber espionage) is considered generally just the preparation for probable future cyber attack operations, since cyber reconnaissance very easily transforms into cyberspace attack, if one only presses a button. For instance, the code for Chinese cyber weapons used in espionage and offensive operations doesn’t differentiate clearly between reconnaissance and offensive functions; rather, those functions often tend to be integrated within a single cyber tool. The PLA presents the concept of integrated reconnaissance, attack, and defense (偵攻防一體), implying that the operational activities of Chinese cyber forces would likely take a less differentiated approach to these activities, which are inherently interrelated at the technical level. Such operational integration, even if not directly proscribed by existing and nascent legal and normative frameworks, could raise the risks of misperception or misattribution of intent in a crisis scenario, given the lack of technical differentiation between ordinary cyber espionage and cyber preparation of the battlefield.

Focused on Supporting Conventional Operations

The PLA elevated cyber operations under the SSF in December 2015, placing the virtual domain on par with other branches of the military. Chinese cyber warfare will be focused on supporting conventional military operations as opposed to assuming an independent role in strategic warfare, as US Cyber Command seems to be doing, or to bolster information operations, as Russia seems to be doing. The US may use its cyber capabilities for “left-of-launch” missile defense against North Korea—meaning, sabotaging planned missile launches before they happen—and to disrupt IS (Islamic State) communications. By contrast, China is consumed by fears of a massive US military intervention in Asia. Beijing is building up its anti-access and area denial (A2/AD) military strategy in the Taiwan Strait and its near seas (Yellow Sea, East China Sea and South China Sea) by adding cyber and electronic warfare capabilities mesh into what is referred to as “Integrated Network-Electronic Warfare” (網電一體戰). A report published by the NATO Cooperative Cyber Defense Center of Excellence, a Tallinn, Estonia-based think tank, maintains that the PLA units responsible for electronic warfare are taking on the role of running computer network operations as well.[15]

China’s strategy consists of neutralizing the logistics and communications infrastructure that permits US forces to operate far from home and is pursuing the ability to corrupt US information systems—notably, those for military logistics—and disrupt the information links associated with command and control. Such network and electronic attacks could target the US military or regional allies’ early warning radar systems and could cause blind spots in US command and control systems. The PLA could use these blind spots to deploy sorties or launch ballistic missile strike. To accomplish effective cyber attacks on US Command, Control, Communications, Computers, Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (C4ISR) platforms or any advanced systems, the PLA would have to conduct cyber reconnaissance ahead of time. These concepts have also been reflected in the PLA’s recent writings on “network swarming warfare” that envisions future campaigns as “multi-directional maneuvering attacks” conducted in all domains simultaneously: ground, air, sea, space, and cyberspace.

In a potential conflict with Taiwan, for example, the PLA may put a strategic premium on denying, disrupting, deceiving, or destroying Taiwan’s C4ISR systems. This would be followed by the deployment of the PLA’s conventional air wings, precision ballistic missile strikes, and sea power projection platforms—all within the first hours of the conflict. A key target for the PLA, for example, would be the highly-advanced US-made ultra-high frequency (UHF) early warning radar system located on top of Leshan Mountain near the city of Hsinchu. Activated in February 2013, the radar is reportedly capable of detecting flying objects up to 5,000 km away, and provide a six-minute warning in preparation for any surprise missile attack from the Chinese mainland. The radar essentially tracks nearly every sortie of the PLA Air Force flying across Taiwan Strait.[16]

In sum, if a war broke out in the Taiwan Strait, cyber warfare is the PLA’s first attack spear.

Dr. Si-Fu Ou is director of the Division of Advanced Technology and Warfighting Concepts at the Institute for National Defense and Security Research, Taiwan. He was secretary of Mainland Affairs Council, a cabinet-level administrative agency and office of the Deputy Minister of National Defense. He was an Adjunct Assistant Professor of the Graduate Institute of Futures Studies at Tamkang University. Dr. Ou earned his Ph. D. in international relations from University of Miami.

[1] Amy Chang, “Warring State: China’s Cybersecurity Strategy,” Center for New American Security, December 2014, https://s3.amazonaws.com/files.cnas.org/documents/CNAS_ WarringState_Chang_report_010615.pdf?mtime=20160906082142

[2] John Costello, “China’s Strategic Support Force: Testimony to the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission,” February 15, 2018, https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/Costello_Written%20Testimony.pdf

[3] Elizabeth Van Wie David, “China’s Cyberwarfare Finds New Targets,” Fair Observer, October 27, 2017, https://www.fairobserver.com/region/asia_pacific/china-cyberwarfare-cybersecurity-asia-pacific-news-analysis-04253

[4] Zi Yang, “China Is Massively Expanding Its Cyber Capabilities,” National Interest, October 3, 2017, https://nationalinterest.org/blog/the-buzz/china-massively-expanding-its-cyber-capabilities-22577

[5] Mark Pomerleau, “DoD’s Assessment of China’s Information Capabilities,” C4ISRNET, June 7, 2017, https://www.c4isrnet.com/articles/dods-assessment-of-chinas-information-capabilities

[6] Bill Gertz, “China Cyber Spy Chief Revealed,” Washington Times, March 28, 2018, https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2018/mar/28/liu-xiaobei-heads-china-us-hacking-operations

[7] Bill Gertz, “US Trade Report Lays Bare Chinese Government Cyber-Espionage,” Asia Times, March 26, 2018, https://www.atimes.com/article/us-trade-report-lays-bare-chinese-government-cyber-espionage

[8] Elizabeth Van Wie David, “China’s Cyberwarfare Finds New Targets,” Fair Observer, October 27, 2017, https://www.fairobserver.com/region/asia_pacific/china-cyberwarfare-cybersecurity-asia-pacific-news-analysis-04253

[9] Eric Heginbotham et al., The U.S.—China Military Scorecard: Forces, Geography and the Evolving Balance of Power 1996-2017 (California: Santa Monica, 2015), pp. xxii-xxiii.

[10] John Grady, “Panel: China Seeking Dominance over Rivals in Information, Cyber Operations,” USNI News, March 20, 2017, https://news.usni.org/2017/03/20/panel-china-seeking-dominance-rivals-information-cyber-operations

[11] Brad D. Williams, “Expert Details Centrality of Information to China’s Cyber Ops, Security Strategy,” Fifth Domain Cyber, April 27, 2017, https://www.fifthdomain.com/home/2017 /04/27/expert-details-centrality-of-information-to-chinas-cyber-ops-security-strategy

[12] The Information Office of the State Council, “Full Text: China’s Military Strategy,”China Daily, May 26, 2015, http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2015-05/26/content_20820628.htm

[13] Franz-Stefan Gady, “Why the PLA Revealed Its Secret Plans for Cyber War,” The Diplomat, May 24, 2015, https://thediplomat.com/2015/03/why-the-pla-revealed-its-secret-plans-for-cyber-war

[14] Elsa Kania, “A Force for Cyber Anarchy or Cyber Order? —PLA Perspectives on Cyber Rules,” China Brief, July 6, 2016 (Volume: 16, Issue: 11), https://jamestown.org/program/a-force-for-cyber-anarchy-or-cyber-order-pla-perspectives-on-cyber-rules

[15] Levi Maxey, “China’s Pivots Its Hackers from Industrial Spies to Cyber Warriors,” The Cipher Brief, April 2, 2017, http://www.thecipherbrief.com/article/asia/china-pivots-its-hackers-industrial-spies-cyber-warriors-1092

[16] Michael Raska, “China’s Evolving Cyber Warfare Strategies,” Asia Times, March 8, 2017, http://www.atimes.com/article/chinas-evolving-cyber-warfare-strategies