WHY DID RUSSIA’S HYBRID WARFARE FAIL IN ITS INVASION OF UKRAINE 2022?

2023.09.04

Views

1138

INTRODUCTION

The Russian invasion (Vladimir Putin termed it a “special military operation”) of Ukraine since February 24, 2022, has been ongoing for more than a year. Despite the fact that the end is not yet in sight, it is clear that the war scenario has not evolved according to Putin’s initial plan. Over the past months, the firm resistance and resilience of the Ukrainians have offered valuable lessons and inspired many who are fighting against authoritarian regimes, including people of Taiwan. At the same time, the war is also being closely examined by revisionists seeking to reshape the global order, including China.

Analyzing its successful annexation of Crimea in 2014, existing literature reveals that Moscow’s triumph at the time was a result of hybrid warfare tactics. Many analysts have observed that Russia adopted a similar approach towards Ukraine in 2022; however, the Russian effort did not yield the same result. This discrepancy has created an academic gap that this paper aims to address.[1]

This paper argues that, from a theoretical standpoint, hybrid warfare is disruptive due to its nature of employing indirect approaches and non-military actions to menace. However, once Moscow launched a full-scale invasion, the military actions significantly compromised the advantages of hybrid warfare. Furthermore, in 2022, Russia found it difficult to replicate its successful tactics involving disinformation and propaganda, as the Ukrainian people have enhanced their media literacy and awareness based on previous experience. Additionally, they have received external assistance to counter Moscow's information manipulation. As a result, while the cognitive domain used to be a weakness for Ukraine, it has now become a strength.

From below, this paper begins by reviewing the characteristics of hybrid warfare. It then explores the countermeasures developed by Ukraine in response to the Russian operation. The paper acknowledges Moscow’s activities but refrains from delving into detailed discussion, as many existing analyses have already covered those aspects. Instead, it focuses on explaining the reasons behind the failure of Russian hybrid warfare tactics.

HYBRID WARFARE AND ITS INDIRECT APPROACH CHARACTERISTIC

Often referred to as “the smoothest invasion of modern times,”[2] Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 during the EuroMaidan Revolution serves as a notable example of hybrid warfare. The term itself not only holds analytical value but also represents a practical framework that guided Russia’s operations during that period and afterwards.

The theory of hybrid warfare was initially proposed by Frank Hoffman, a US military theorist who generalized a pattern from the armed conflict between Israel and Hezbollah in Lebanon in 2006. He argues that it is a mode blurring lines between actors, tactics, battlefields as well as formations in which high- and low-intensity warfare may occur simultaneously. The concept of hybrid warfare transforms the traditional Western knowledge of warfare. Having witnessed the Russian annexation of Crimea, many analysts including Hoffman suggested that Moscow’s operation featured another example of hybrid warfare, and it showcased further advancements.[3]

Since then, the security studies community has undertaken a reconceptualization of their understanding of hybrid warfare. The European Centre of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats (Hybrid CoE) defines it as “an action…goal is to undermine or harm a target by influencing its decision-making at the local, regional, state or institutional level.” The attacker typically targets vulnerabilities in democratic states and their institutions. These activities can occur across different domains such as political, economic, military, civil, or information.[4]

In another place, NATO suggests that hybrid warfare “entails an interplay or fusion of conventional as well as unconventional instruments of power and tools of subversion” in which “instruments or tools are blended in a synchronized manner to exploit the vulnerabilities of an antagonist and achieve synergistic effects.” Arguably, hybrid warfare is often launched below the threshold of war and avoids overt military attack. With its resulting uncertainties, the adversary is then easily confused and fails to react in a timely way.[5]

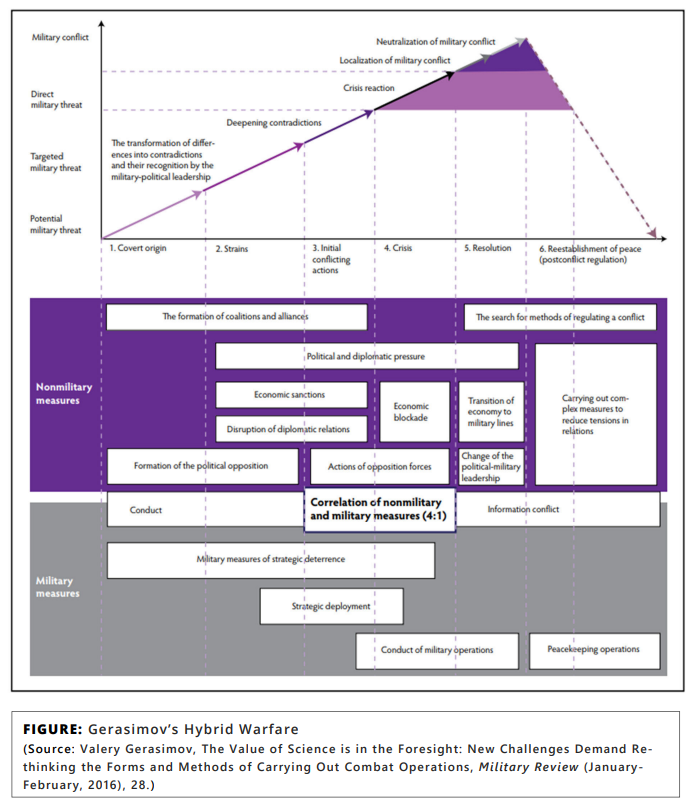

The so called “Gerasimov Doctrine” is a classic theory of Russian hybrid warfare. From the Russian viewpoint, many cases of regime change in the post-Soviet era were in fact related to the US and West; these cases included the NATO’s Yugoslavia intervention, Color Revolution, and the Arab Spring. Arguably, the West’s operations can be divided into three main phases. First of all, the West sought to install political opposition, nongovernmental organizations, and media. Secondly, the creation of political dissent and voices destabilizing local social order, and then the imposition of economic, political, and even military activities when acquiring a window of opportunity. Eventually, the building of a friendly regime.[6]

Referring to a graphic (see Table 1), it is clear that the “Gerasimov Doctrine” integrates the previous experiences and conceptualizes a conflict into multiple stages and highlights indirect and asymmetric thinking. It underlines power from conflating non-military and military measures, roughly a four-to-one ratio. Between both, information plays a significant role as a weapon and in its own right. Furthermore, through amplifying the existing societal, political, economic, cultural, or ideological divisions in the target society, the Doctrine intends to undermine the society’s cohesion and resilience. Importantly, hybrid warfare always seeks tailored breach of the vulnerabilities of the target society.

In its substance, hybrid warfare shares many ideas with Liddell Hart’s “indirect approach” at both strategic level and tactical levels. According to his theory, the true gauge of an indirect approach is seeking to disturb the opponents’ and thus throw them off balance. Informational method is a crucial aspect. Similarly, Sun Tzu in The Art of War also underscores the advantages of an indirect approach. While these concepts and theories were developed in different contexts, they all touch upon the argument that a direct approach easily lacks adaptability and flexibility, leading to the exhaustion of the attacker and provoking counterattacks.[7]

Applying the concept to analyze the Crimea crisis, Russia utilized various tools such as the Internet, social media, and propaganda systems, alongside a covert invasion. These actions align closely with the principles of hybrid warfare. Moscow expected to replicate its previous success in 2022. Prior to the military attack in February, it disseminated pro-Russian messages and narratives, planned false-flag activities, and engaged in cyberattacks targeting local critical infrastructure.[8] However, as Russia relied on physical attacks, the situation may not entirely fit within the framework of hybrid warfare. Furthermore, with accumulated experience from events since 2014, the Ukrainians have developed enhanced capabilities to counter Russian aggression and address their informational strategies. The following section will delve further into this discussion.

UKRAINIAN COUNTERMEASURES AGAINST RUSSIAN INFORMATION MANIPULATION AND COGNITIVE WARFARE

After the loss of Crimea, Ukraine continued to face a relentless onslaught of information attacks. These included the dissemination of fake news and disinformation by pro-Russian news media and social networking platforms, cyberattacks launched by hackers targeting governmental agencies and Ukraine’s critical infrastructure, and military-sponsored separatism in Donbass, Eastern Ukraine. These coordinated activities aimed to undermine the security of state and society, creating a pervasive sense of uncertainty and fear while justifying Russian encroachments on Ukraine’s sovereignty since 2014. The Kremlin skillfully crafted narratives and propagated them not only through Russian state-controlled media and networks but also through local collaborators in Ukraine who infiltrated social spaces widely-used by Ukrainians.

To mitigate the potentially negative impacts, the former administration of Petro Poroshenko banned social media and other Internet resources and software from Russia. Many NGOs also promoted media literacy in the civil areas.[9]

Due to prolonged exposure to Russian disinformation, it can generally be said that most Ukrainians have developed the ability to discern between true stories and pro-Kremlin propaganda and disinformation claims, especially when it comes to political topics. In recent years, Ukraine-based fact-checking organizations such as Ukraine Today, StopFake, VoxCheck have been established and have expanded their interaction and collaboration with the EU- and NATO- sponsored agencies, exchanging experiences and measures against Russian deceptions. After the war of 2022 broke out, some also built connections to Taiwan which has gained rich experience of countering China’s hybrid threat challenges and gray-zone operations.[10]

Asked about whether the US Department of Defense has capabilities to tackle the hybrid threats, Christopher S. Chivvis, then deputy head of the RAND Corporation’s international security program of the House of Representatives, outlined a list of elements, ranging from interagency coordination and support for European countering of Russian operations, in addition to the continued investment in conventional forces.[11] We saw the US achieved their commitments.

Prior to the war, the US and NATO set up a variety of teams and programs helping Ukraine to train and improve it capabilities to better deal with the Russian challenges. Also, the NATO and the EU established the Hybrid CoE to develop intellectual and practical policies and measure proposals to counter the hybrid threats which Ukraine faces. Such assistance is valuable in fostering Ukrainian resilience at governmental and civil levels. At the same time, they have built confidence in integration with Europe and believe that they receive support from the West.

At the onset of the war, Russia exerted its leverage through waves of distributed denial-of-service attacks (DDoS), ransomware attacks, and internet-based disinformation campaigns targeting critical infrastructure and civilians. The intention behind these kinetic activities was to exploit the ensuing chaos. Echoing Putin’s speeches and narratives, Russia’s initial objective was to incapacitate Ukrainian defenses and ultimately take control of the entire country in a short time. However, the actual scenario played out quite differently.

In the face of violent assaults, the Ukrainian people stood their ground. Governmental and civil channels persevered, ensuring the delivery of messages to both the public and the outside world. They capitalized on various social media platforms, such as Facebook (FB), Instagram (IG), Telegram (TG), and Twitter, where numerous channels and groups were created, numbering in the thousands. Volodymyr Zelensky and senior officials frequently released recordings and posts on social media to clarify the situation and progress on the battlefield. Mykhailo Fedorov, the Minister of Digital Transformation and First Vice Prime Minister, called for volunteers to form a Ukrainian IT army and join the fighting. The request received a great response, one of them from the hacking collective Anonymous. Fedorov also posted his request on Twitter, appealing to Elon Musk to provide the Starlink service and then receiving a positive answer.[12] This low-orbit satellite internet has made an invaluable contribution to the Ukrainians in terms of maintaining daily communications and allowing forces to keep fighting on the frontlines.

With these commitments, the Ukrainian people were not only motivated to maintain a high degree of resistance but also succeeded in forging a sophisticated global network to seek external support and exert pressure on Russia. Simultaneously, Ukrainian sources often highlighted the challenging circumstances and low morale of Russian soldiers as part of their psychological warfare strategy. This approach served to reinforce the determination of the Ukrainian people. Through the use of pictures, videos, and words, Ukrainians not only obtained accurate information but also reached out to the world for support. As a result, the Ukrainian voice and message have become a potent weapon against Russia, which has been at a disadvantage on the information battlefield.

CONCLUSION

While much of the existing literature agrees that Russia employed hybrid warfare during its invasion in 2022, there were distinct differences in emphasis compared to the activities observed in 2014 when Putin launched the “special military operation.” In the recent invasion, Russia indeed employed non-military means such as cyberattacks, disinformation campaigns, and cognitive warfare, alongside blatant military action to occupy Ukrainian territory. Faced with this urgent crisis, the Ukrainian government and civil society demonstrated unity and refused to accept any excuse that sought to legitimize the invasion.

Interestingly, Moscow’s preference for violence over other covert informational means to undermine Ukraine's sovereignty has transformed its previous indirect approach of hybrid warfare, as witnessed in 2014, into a more direct approach. In the earlier instance, Russia deployed only a small number of troops and extensively exploited domestic divisions surrounding pro-EU and pro-Russia diplomacy, as well as ethnic conflicts within Ukraine, to intervene in the state. In the cognitive domain, the Kremlin deceitfully manipulated the sense of insecurity and uncertainty to advance its interests. However, prioritizing the military now is likely to backfire, rendering other efforts futile. The Ukrainian people have formed a unified aversion to the invasion and possess unwavering determination to resist.

Recalling one of the principles in Liddell Hart’s theory, “do not attack if your enemy is on guard,” it has become evident that Russian aggression has proven ineffective and only served to strengthen the will of the Ukrainian people. With continued support from the international community, there is no doubt that Ukraine will not make any concessions. Consequently, the ongoing Russian-Ukrainian war will be a contest of pure force.

Dr. Tsung-Han Wu is an Assistant Research Fellow at Division of Cyber Security and Decision-Making Simulation, INDSR. His research interests include Cybersecurity, Cognitive Warfare, International Relations, and Chinese Politics.

[1]What is hybrid war, and is Russia waging it in Ukraine?,” The Economist, February 22, 2022, https://www.economist.com/the-economist-explains/2022/02/22/what-is-hybrid-war-and-is-russia-waging-it-in-ukraine; Weilong Kong and Tim Marler, “Ukraine’s Lessons for the Future of Hybrid Warfare,” The Nationalist Interest, November 25, 2022, https://nationalinterest.org/feature/ukraine%E2%80%99s-lessons-future-hybrid-warfare-205922.

[2] Kishika Mahajan, “Russia’s hybrid warfare strategy: From Crimea to Ukraine,” ORF, March 1, 2022, https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/russias-hybrid-warfare-strategy/.

[3]Frank Hoffman, “On Not-so-new Warfare: Political Warfare VS Hybrid Threats,” War on the Rocks, July 28, 2014, https://warontherocks.com/2014/07/on-not-so-new-warfare-political-warfare-vs-hybrid-threats/.

[4]“Hybrid threats as a concept,” Hybrid CoE, https://www.hybridcoe.fi/hybrid-threats-as-a-phenomenon/.

[5]Arsalan Bilal, “Hybrid Warfare – New Threats, Complexity, and ‘Trust’ as the Antidote,” NATO Review, November 30, 2021, https://www.nato.int/docu/review/articles/2021/11/30/hybrid-warfare-new-threats-complexity-and-trust-asthe-antidote/index.html.

[6]Charles Bartles, Getting Gerasimov Right, Military Review (January-February 2016), 31-33.

[7]Sibylle Scheipers, “Winning Wars without Battles: Hybrid Warfare and Other Indirect Approaches in the History of Strategic Thought,” in Russia and Hybrid Warfare-Going Beyond the Label (Finland: Aleksanteri Institute: 2016), 48-50.

[8]Davey Alba, “Russia has been laying groundwork online for a ‘false flag’ operation, misinformation researchers say,” The New York Times, February 19, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/02/19/business/russia-has-been-laying-groundwork-online-for-a-false-flag-operation-misinformation-researchers-say.html; Frank Hofmann, “Hybrid war began before Russian invasion,” DW, February 25, 2022, https://www.dw.com/en/hybrid-war-in-ukraine-beganbefore-russian-invasion/a-60914988.

[9]Reuters Staff, “Ukraine slaps sanctions on Russia's Yandex, other web businesses,” Reuters, May 16, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/ukraine-crisis-sanctions-idUKL8N1II24F; “Enhancing media literacy in Ukraine during the Russian aggression,” International Information Academy, April 10, 2019, https://interacademy.info/en/enhancing-media-literacy-in-ukraine-during-the-russian-aggression/

[10] “85 guo gong zhu zi xun zhan quan qiu fang xian 5423 ze cha he bao gao di yu zhan shi bu shi xun xi” [85 國共 築資訊戰全球防線 5423則查核報告抵禦戰事不實訊息 85 Countries Jointly Build Global Defense Line of Information Warfare Completing 5423 Fact-checking Reports Against Disinformation], Taiwan FactCheck Center, February 24, 2023, https://tfc-taiwan.org.tw/articles/8841.

[11]Christopher S. Chivvis, “Understanding Russian ‘Hybrid Warfare’ And What Can Be Done About It,” RAND, March 22, 2017, https://www.rand.org/pubs/testimonies/CT468.html.

[12]Dan Milmo, “Anonymous: the hacker collective that has declared cyberwar on Russia,” The Guardian, February 27, 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/feb/27/anonymous-the-hacker-collective-that-has-declaredcyberwar-on-russia; “Elon Musk says Starlink internet service ‘active’ in Ukraine,” Aljazeera, February 27, 2022, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/2/27/elon-musk-starlink-internet-service-ukraine-russian-invasion.